Many fledgling neuroscientists who are eager to dive deep into the statistical analysis of functional MRI data know of Martin Lindquist. Martin is a professor in the department of biostatistics at the Johns Hopkins University. His popular “Principles of fMRI” Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) and associated book have reached an audience of more than 80,000 students worldwide. Our interview with Martin follows his path through various academic disciplines, eventually leading him towards educating the current generation of neuroimagers and winning the 2018 OHBM Education in Neuroimaging Award.

0 Comments

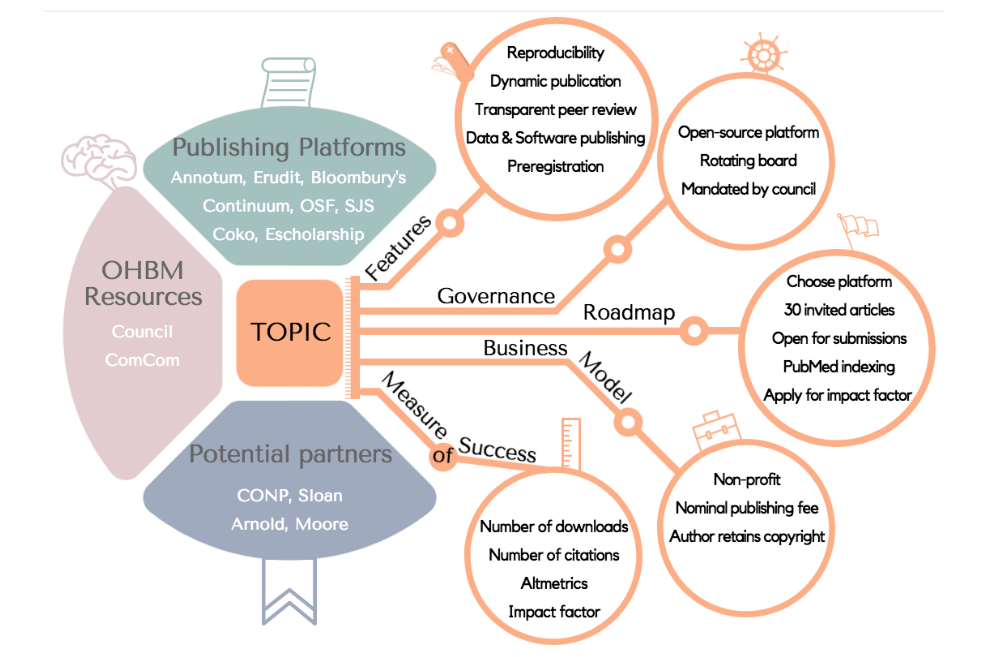

OHBM plans to create a new publishing platform, Aperture, to host high-quality research objects while promoting reproducible and open science. With Aperture, OHBM plans to open up to a more diverse approach in communicating academic research, bringing transparency and interactivity to the publishing process. We want to hear from you, the OHBM community, about what you would like to see in such a publishing platform. Please complete the survey by clicking here.  The OHBM Publishing Initiative Committee (TOPIC) will be introducing a new journal, called Aperture. The roadmap above is tentative, and it was presented to council in 2017 to illustrate the various aspects of the project led by the OHBM Publishing Initiative Committee (TOPIC). Credit: Agah Karakuzu For more information about the processes behind publications, read through this explainer by Michael Breakspear.

By Elizabeth DuPre; Edited by Aman Badhwar What exactly is “open science”? As open science has become increasingly central to discussions of scientific practice, publishing, and policy, it’s become harder to provide a precise definition that encompasses all of its aims. The ubiquitous nature of open science is at once its greatest strength and deepest weakness -- it’s broadly useful, but difficult to distill as a clear set of values or prescriptions. It’s been said that one way to get a better sense of a movement is to talk to its supporters, so I turned to some of the newest advocates for open science within OHBM: the newly elected members of the Open Science Special Interest Group (OSSIG) committee. I asked for their thoughts on what open science means, how they got involved in promoting open science initiatives, and why they’re so passionate about increasing its reach within our community. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed