|

By Claude Bajada, Simon M. Hofmann and Ilona Lipp

Edited by: Thomas Yeo and Lisa Nickerson Machine learning, deep learning and artificial intelligence are terms that currently appear everywhere; in the media, in job adverts… and at neuroimaging conferences. Machine learning is often portrayed as a mystical black box that will either solve all our problems in the future or replace us in our jobs. In this blog post, we discuss what the term machine learning actually means, what methods it encompasses, and how these methods can be applied to brain imaging analysis. Doing this, we refer to the OHBM OnDemand material, which contains some great videos explaining machine learning methodology and we provide examples for how it has been used in a variety of applications. If you are curious about machine learning tools, but are not really sure whether you want to jump on the bandwagon, then we hope that this post is right for you and will help you get started. What is machine learning?

2 Comments

Professor David Kennedy is a Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts. He was a key contributor to the development of functional MRI and diffusion MRI, working in MGH during the late 80s and 90s. His current work reflects his interests in Neuroinformatics and data sharing - indeed he is a founding editor of the journal Neuroinformatics. We found out about his experiences with OHBM, and some of the deep and lasting friendships he made along the way.

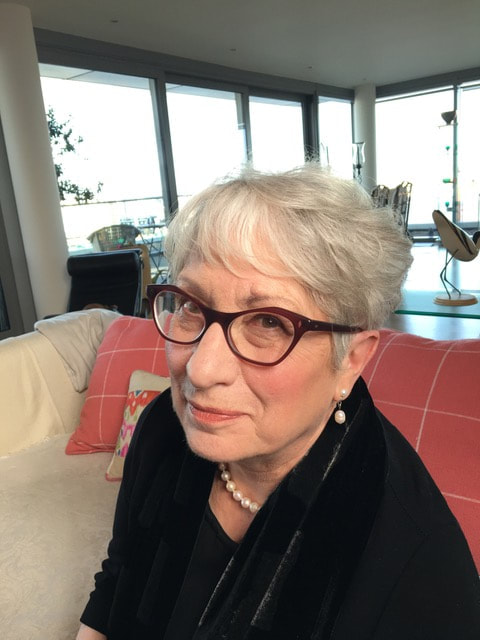

By Kirstie Whitaker Open science means different things to different people. It includes open data, open source code, preprints, preregistrations, and open access publications. Getting started with open science practices can be overwhelming, and there is considerable variability in their adoption across the OHBM community. I sat down with Tibor Auer to learn about the survey he has developed to capture different attitudes towards open science practices in order to better support everyone in doing the best research they can.  Dr Tibor Auer Dr Tibor Auer Hi Tibor, let’s get started with an easy question: who are you? I am a Research Fellow in MRI at the Department of Psychology, Royal Holloway University of London, where I facilitate neuroimaging by contributing to methods innovation, as well as training and education. Neurofeedback is one of my main research interests, as it offers the opportunity to follow neural development during the training process, thus satisfying interest in both theory and application. I received my PhD in clinical neuroscience and implemented various neuroimaging techniques in a clinical environment. Then, I focused on the implementation and the optimization of fMRI-based neurofeedback, and investigated assumptions and mechanisms underlying a neurofeedback training. By Amanpreet Badhwar and the Diversity and Gender Committee The OHBM Diversity and Gender Committee is performing a series of interviews to better understand and address the issues of implicit and explicit biases in academia. The ultimate goal is to promote gender and geographic balance and create a more inclusive brain mapping community. Over the next months we will be interviewing social psychologists and social neuroscientists to get multiple perspectives on the topic. We start this series by interviewing Uta Frith.  Professor Uta Frith Professor Uta Frith Aman Badhwar (AB): How did you get into social psychology and neuroscience? Are there any personal experiences that motivated you? Uta Frith (UF): When I left school for university, way back in the 1960s, in provincial Germany, I had never heard of neuroscience, and I wasn’t sure that psychology was a respectable subject to study. I more or less drifted into psychology and one reason was that I was curious to learn about myself and about other people. But that, I soon gathered, was considered the worst possible motivation for taking up psychology! Instead I could learn about memory, perception and attention. It sounded a bit dreary, but I persevered. I was not disappointed. At the University of Saarbrücken, I discovered that there are millions of questions about the mind and the brain, but the most interesting ones came from some vivid case demonstrations in the psychiatric clinic. I therefore decided to take up training in clinical psychology and was lucky to get a place at the Institute of Psychiatry in London. But it was by chance that I met an autistic child right at the beginning of my training. This five-year-old boy was supremely uninterested in me, but very interested in bricks and puzzles. I was captivated by the strange contrast of abilities and disabilities. It made me determined to find out what might go on in the mind/brain of this little boy. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed