|

BY KEVIN WEINER New OHBM Communications Committee article on HuffPost Science: It’s often hard to find easy-to-read articles about cool scientific findings that are written in a clear way - let alone articles that are understandable enough to use as bedtime reading with your child. But, here’s a little secret: there are articles out there that are actually written by scientists and approved by children before they are published. Read more

0 Comments

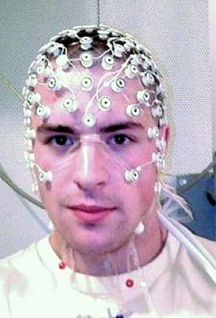

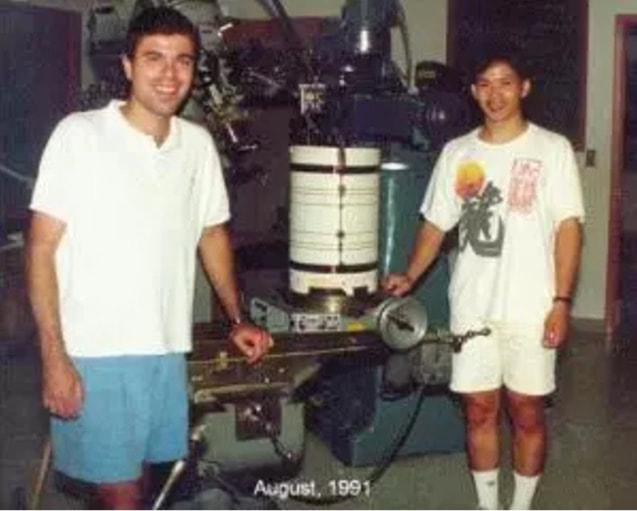

Research participant with EEG Research participant with EEG BY LEONARDO FERNANDINO For over two decades functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been the indisputable workhorse in human brain mapping. Its ability to localize brain activity with high spatial resolution (millimeters), coupled with its non-invasiveness, make it an excellent tool for mapping behavioral and cognitive phenomena onto detailed brain anatomy. However, since fMRI relies on changes in blood flow, volume and oxygen concentration as indicators of neural activity, millisecond-scale fluctuations in neuronal activity are not reflected in the signal. The temporal resolution of fMRI (typically > 500 ms) is therefore too coarse to track neural activity in real time and discriminate rapidly succeeding neural events. For example, some fMRI studies indicate that auditory cortical activations in response to signed language are stronger in deaf participants than in hearing individuals, raising the possibility that the auditory cortex is rewired to process visual information in deaf individuals. An alternative interpretation, however, is that visual processing of sign language occurs entirely in the visual cortex for both groups, and that activations in the auditory cortex reflect only a later, conceptual processing stage. The speed with which these processes occur makes it challenging to determine the precise sequence in which different brain regions become active using fMRI (or any other method that relies on metabolic responses, such as fNIRS or PET). Fortunately, other non-invasive techniques can provide such precise temporal information. Electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) directly track the electrical activity of brain cells by measuring its effects on the electrical and magnetic fields just outside the head. They allow researchers to record brain activity at a very high temporal resolution (milliseconds), close to the actual timescale of neural computations. EEG measures changes in electrical potential generated by the brain, which reflect the bulk electrical activity of many pyramidal neurons depolarizing in synchrony, through electrode leads placed on the scalp and connected to an amplifier. Researchers can then estimate the locations of the neural sources of these signals. The accuracy of these estimates depends, among other things, on the number of electrodes used, with higher numbers resulting in more precise estimates. Typically, between 64 and 256 electrodes are used. BY GUEST AUTHOR R. ALLEN WAGGONER I had the honor of knowing Dr. Kang Cheng not only as a scientific colleague, but also as one of my closest friends for more than 20 years. He was the picture of health, so I was as stunned as everyone else when I learned that he has passed away suddenly at the age of 54. He left behind his wife, Professor Mariko Miyata, and their young son Kai.  Dr. Kang Cheng Dr. Kang Cheng Kang was born in Ningbo, China, in the province of Zhejiang, in 1962. He did not start out as a neuroscientist but graduated from Zhejiang University in 1983, with a B.A. in Geology. After graduating, Kang worked at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu Institute of Geography for six years, doing image processing of satellite images. His work in image processing led to several opportunities to come to RIKEN (The Institute for Physical and Chemical Research, in Wako-shi Japan) for short visits. One of those visits was in a neuroscience lab, the Information Science Laboratory, headed by Dr. Keiji Tanaka. Dr. Tanaka offered Kang the opportunity to join the lab on a more permanent basis, if he was interested in becoming a neuroscientist. Kang accepted this offer and moved to Japan in 1989. BY GUEST AUTHOR PETER BANDETTINI This post originally appeared on The Brain Blog by Peter Bandettini and Eric Wong. Republished with permission. I’ve been working to advance Functional MRI (fMRI) since its inception. On Sept 14, 1991, two years into graduate school, and a month after seeing preliminary Massachusetts General Hospital results at the SMR meeting in San Francisco, Eric Wong and I performed our first successful fMRI experiment (Bandettini 2012).

The Brain Connectivity & Behaviour group (from left to right, Emmanuelle Volle, Chris Foulon, Michel Thiebaut de Schotten, Marika Urbanski, Leonardo Cerliani, Marine Lunven). The Brain Connectivity & Behaviour group (from left to right, Emmanuelle Volle, Chris Foulon, Michel Thiebaut de Schotten, Marika Urbanski, Leonardo Cerliani, Marine Lunven). BY NILS MUHLERT Many neuroimaging projects are multi-disciplinary. They often involve collaborations between physicists, engineers, computer scientists, biologists, cognitive scientists, and clinicians amongst others. Inevitably, this leads some to go well beyond their core discipline, learning and making notable advances in complementary fields. Michel Thiebaut de Schotten’s career falls firmly within this camp. With a background in Psychology, Michel went on to make substantial advances in neurobiology and neuropsychiatry, co-authoring a fundamental book on white matter anatomy (Atlas of Human Brain Connections), and papers on the anatomy of spatial neglect, attention and word reading ability, before reinterpreting and re-analysing data from historical case studies in neurology. This breadth of experience lends itself well to OHBM, a society that provides a bridge between disciplines.  Tzipi Horowitz-Kraus and Karl Friston Tzipi Horowitz-Kraus and Karl Friston BY TZIPI HOROWITZ-KRAUS Read Part 1 of this interview here. Tzipi Horowitz-Kraus (THK): What do you consider to be the greatest scientific discovery that was made possible by neuroimaging? Karl Friston (KF): That's a difficult question. I think we all have to acknowledge that there is no field in systems neuroscience that hasn't been profoundly touched by neuroimaging. However, I think the impact and import of neuroimaging is not about discovery, it is seismic in a slower and subtler way; basically, neuroimaging makes a lot of sense of stuff that we already knew. In other words, I would not point to what has been discovered as the validation of brain mapping but point to how it makes sense of the vast amount of knowledge that has been accrued through the centuries of anatomy, physiology and psychology. We knew a lot of things in the past but now we know how to put them together. Neuroimaging can contextualize mesoscopic – and indeed synaptic or molecular – findings and say why that is important and how it relates to this, and how those findings could drive the next wave of imaging neuroscience. THK: What do you think are the most pressing issues in neuroimaging for your area of interest? KF: More detailed and mechanistic modeling of distributed neuronal responses. For instance, getting the right kind of connectivity and determining how to best integrate structural and functional connectivity. Other issues include connecting behavior to physiology and connecting functional connectivity to the underlying synaptic processing, and connecting synaptic processing to microcircuits – and microcircuits to whole brain connectomes. When people ask me “What is the most important issue for you?” I respond "the issues that I work on"; namely, biophysical modeling (at least in my day job). In short, getting better and better modeling tools that enable people to ask evidence-based questions about the mechanisms that underlie the functional integration they are interested in. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed