|

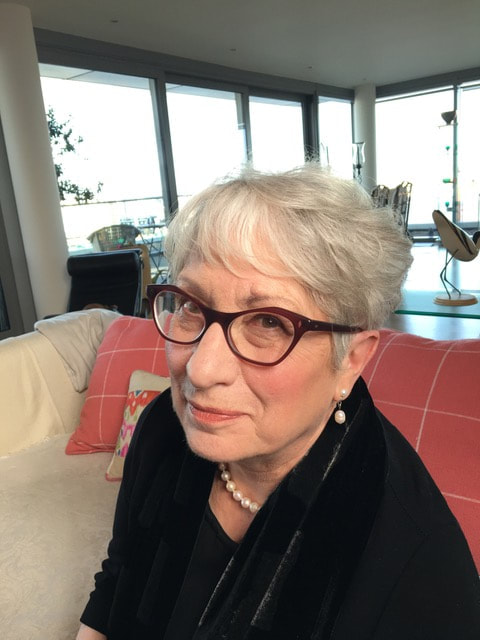

By Amanpreet Badhwar and the Diversity and Gender Committee The OHBM Diversity and Gender Committee is performing a series of interviews to better understand and address the issues of implicit and explicit biases in academia. The ultimate goal is to promote gender and geographic balance and create a more inclusive brain mapping community. Over the next months we will be interviewing social psychologists and social neuroscientists to get multiple perspectives on the topic. We start this series by interviewing Uta Frith.  Professor Uta Frith Professor Uta Frith Aman Badhwar (AB): How did you get into social psychology and neuroscience? Are there any personal experiences that motivated you? Uta Frith (UF): When I left school for university, way back in the 1960s, in provincial Germany, I had never heard of neuroscience, and I wasn’t sure that psychology was a respectable subject to study. I more or less drifted into psychology and one reason was that I was curious to learn about myself and about other people. But that, I soon gathered, was considered the worst possible motivation for taking up psychology! Instead I could learn about memory, perception and attention. It sounded a bit dreary, but I persevered. I was not disappointed. At the University of Saarbrücken, I discovered that there are millions of questions about the mind and the brain, but the most interesting ones came from some vivid case demonstrations in the psychiatric clinic. I therefore decided to take up training in clinical psychology and was lucky to get a place at the Institute of Psychiatry in London. But it was by chance that I met an autistic child right at the beginning of my training. This five-year-old boy was supremely uninterested in me, but very interested in bricks and puzzles. I was captivated by the strange contrast of abilities and disabilities. It made me determined to find out what might go on in the mind/brain of this little boy. I never tired of doing research on autism and it taught me a lot about myself. As a child of my time, I had believed that it was my social environment that had turned me into a person keenly interested in other people. Now I had to entertain the notion that social interaction is possible only because of a built-in part of the human brain, and that if this part does not work, the result is autism.

Autism provided a way to probe the question ‘what makes human communication special’. In the 1980s a group of us tested the theory that a cognitive mechanism, we termed mentalising, enables us to attribute mental states to ourselves and others, and is crucial for reciprocal communication. It still feeds my sense of wonder that this cognitive mechanism is at the basis of human cooperation and reputation, as well as competition and deception. AB: Women haven’t always received appropriate recognition for their work. How have you seen opportunities for women change? A change in climate? Is there a similar trend for women of colour? UF: I grew up at a time of strong gender stereotypes and I was thoroughly imbued with them. My mother, born 1907, did not have a higher education, - it simply wasn’t even considered at the time. However, she managed to educate herself. At age eleven or so I begged my parents to send me to an academically challenging school that was then aimed at boys who would go on to University. The general view at the time was that girls should get a good all-round education at secondary school, then do something useful before getting married, such as becoming teachers or nurses. A few girls at my school were happily tolerated as oddballs or ‘bluestockings’. Since we were not conforming to the prevailing gender stereotype, we were having to shape our own role and station in life. I was diligent and ambitious, and I was sure that I would be able to take up any career I wanted. I don’t know where this confidence came from. Perhaps one reason was that my parents had confidence in me and always supported my choices. I am very aware of the long history of the struggle for women’s rights. I am proud that in the last 100 years women in Western societies have won rights that previously were reserved for men. The fact that the inequality and inferiority of women has been seen as unsupportable, morally and economically, has changed the cultural climate. Now we need to work towards this change for every part of the world, not just for a few privileged parts. However, there are still barriers even in privileged societies. For example, it is harder to enter an academic career if your social background leaves you ignorant or suspicious of the world of academia. And then there is still the glass ceiling! While women in the UK now make up almost a quarter of professors, when we take all universities and all disciplines together, women of colour make up a vanishingly small fraction. What is remarkable, is that women of colour have provided some of the most inspiring role models for women in science and technology in recent times – think of the success of the film Hidden Figures. AB: What aspects related to gender differences within the work setting have not changed, but should? UF: The first thing that comes to mind is the gender pay gap. Many organisations are now committed to close this gap, and they are deeply embarrassed if the gap is large. It would be a great injustice if women would not get the same pay, the same status, the same rewards for doing the same jobs as men. But this is a remarkably complicated issue, and it is not always easy to know what is the ‘same job’. I remember being surprised on discovering, when I became a professor, that my salary was lower than that of other professors. But then, I loved my job as a Medical Research Council scientist. It allowed me to dedicate myself entirely to research. I did not envy the administrative responsibilities or teaching duties that the higher paid professors had to do. There are differences in our individual preferences and also abilities. I suppose these might correlate with gender differences to some extent. But individual differences trump gender differences. If you take only averages and forget about distributions and individual differences, then gender differences will emerge in some more or less relevant variables. Their importance depends on culture and context. I like to quote the example of a highly significant gender difference that exists in the ability to throw a ball. Women are far worse at this than men. In situations where women compete with men, strengths and weaknesses associated with gender stereotypes often come to the fore. These can be quite ambiguous, sometimes harmless and sometimes treacherous, and therefore very suitable for sexist jokes. Q: “Is Google male or female?” A: “Female, because it doesn't let you finish a sentence before making a suggestion.” This makes me smile because it refers to a well-known stereotype but also contains a backhanded compliment – interrupting boring talk is surely better than meekly listening. But I can also see the exasperating side of making clever suggestions. Of course, mostly, prejudices are not funny and can have serious consequences, for example in the selection of people given awards, or grants, or simply being invited to give talks. One thing we have learned from social cognitive neuroscience is that we cannot help identifying ourselves with a group, our ingroup. The reverse side of the coin is disrespecting an outgroup. The image we build of ourselves, and the confidence we have in ourselves feed on group alliance and group discrimination. None of us want to be seen as outsiders. We relish the approval of our ingroup and we perfectly understand if we are not exactly loved by the outgroup. In the work setting there continues to be prejudices about gender differences that keep women down, or in their place, as some would have it. Early career researchers are necessarily at a stage of their life when they have to build up a family, and this almost always means a bigger burden on women than men. I am very glad to note that the younger generation of men are now taking up more of the burden. But this is still far from being the norm. Is it possible to get rid of prejudices? Not really. I think that getting rid of one prejudice may well mean acquiring another. We have to use shortcuts when making fast decisions, or else we may never decide anything. AB: Should there be more attention to microaggressions in the workplace, or at conferences? For example, ignoring or minimising ideas, claiming others’ ideas, assuming stereotypic roles. Have these reduced over time? Or increased with decrease of overt aggression? UF: Wouldn’t it be great if we all became nicer people, more kind to each other and more tolerant? But that is a pipedream. We are shaped by evolution to be aggressive as well as benign, to be selfish as well as altruistic. I personally find it a satisfying side effect of getting older that competitiveness declines, and that with it the related emotions, such as pride, envy, revenge, or triumph, seem to decline as well. Sadly, I see less sign that my propensity for discriminating ingroups and outgroups declines with age. Forms of aggression and selfish behaviour are expressed differently in different cultures, and there are subtle expectations that women should be less aggressive. They are also suspected of feeling offended more easily. Women can work against these stereotypes, and in particular not being afraid of giving and taking criticism. Academic life involves a lot of critique and judgment. It is hard to take justified critique and easy to take it for unjustified aggression. The main danger in my view is to feel offended when we shouldn’t be. Above all, we should not get drawn into retaliation. Empirical studies show that retaliation leads to escalation. Hence my advice would be that monitoring should be less zealous when registering aggressions, including micro-ones, and more zealous when gauging the appropriate reactions to aggressions. Any monitoring is best done in diverse groups. With different backgrounds we have different perspectives, and we can see each other’s flaws much better than we can see our own. AB: What tips would you give for young investigators, irrespective of their own gender to better understand gender biases, and to make changes? UF: My main tip is to discuss and to argue freely any differences of opinion about whether some things are more suitable for men or for women. Take the opposite view and try the argument from the other side. Arguments are a good thing for scientists. We need diversity or else we can easily get stuck in a dead end. I tend to think that complementarity of social roles and fairness to all should be celebrated over a relentless quest for equality. We are all different! Research needs different types of people, different skills, different outlooks and collaboration as well as competition. There are conflicts, and research tells us that transgressions need to be punished, or else cooperation collapses. But punishment is a dangerous thing. The danger is retaliation and escalation. So what to do? Rules of politeness have been set up for good reason and I recommend anyone to value them and not throw them aside as old fashioned. My advice goes further: try to be more than polite and try to be kind and forgiving! Of course, there will always be people who will do something that has rightly offended you or disadvantaged you in some way. But remember others may experience the same from you, even if you feel that you never gave cause for offence. Our self-bias makes this so. AB: Are there any specific gender biases that earlier were advantageous for women, that are now gone? UF: I can’t think of any. AB: Thank you Uta for taking the time to provide such insight into the various topics. I really look forward to seeing you at OHBM 2019 in Rome! Note: AB is also a member of the OHBM Diversity and Gender Committee.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed