|

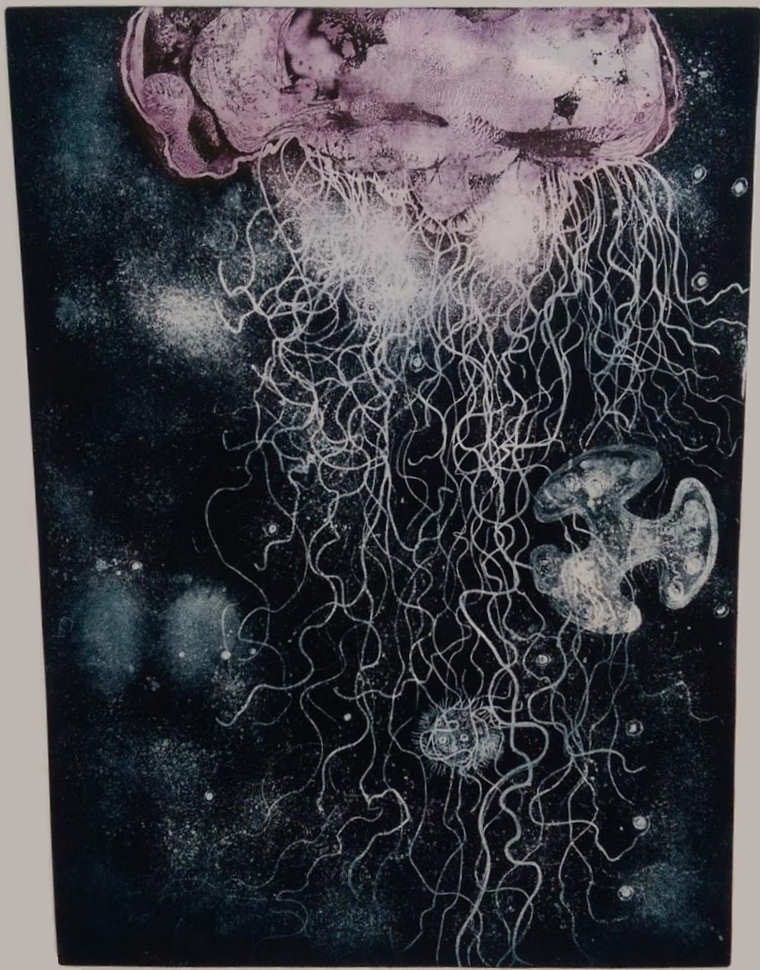

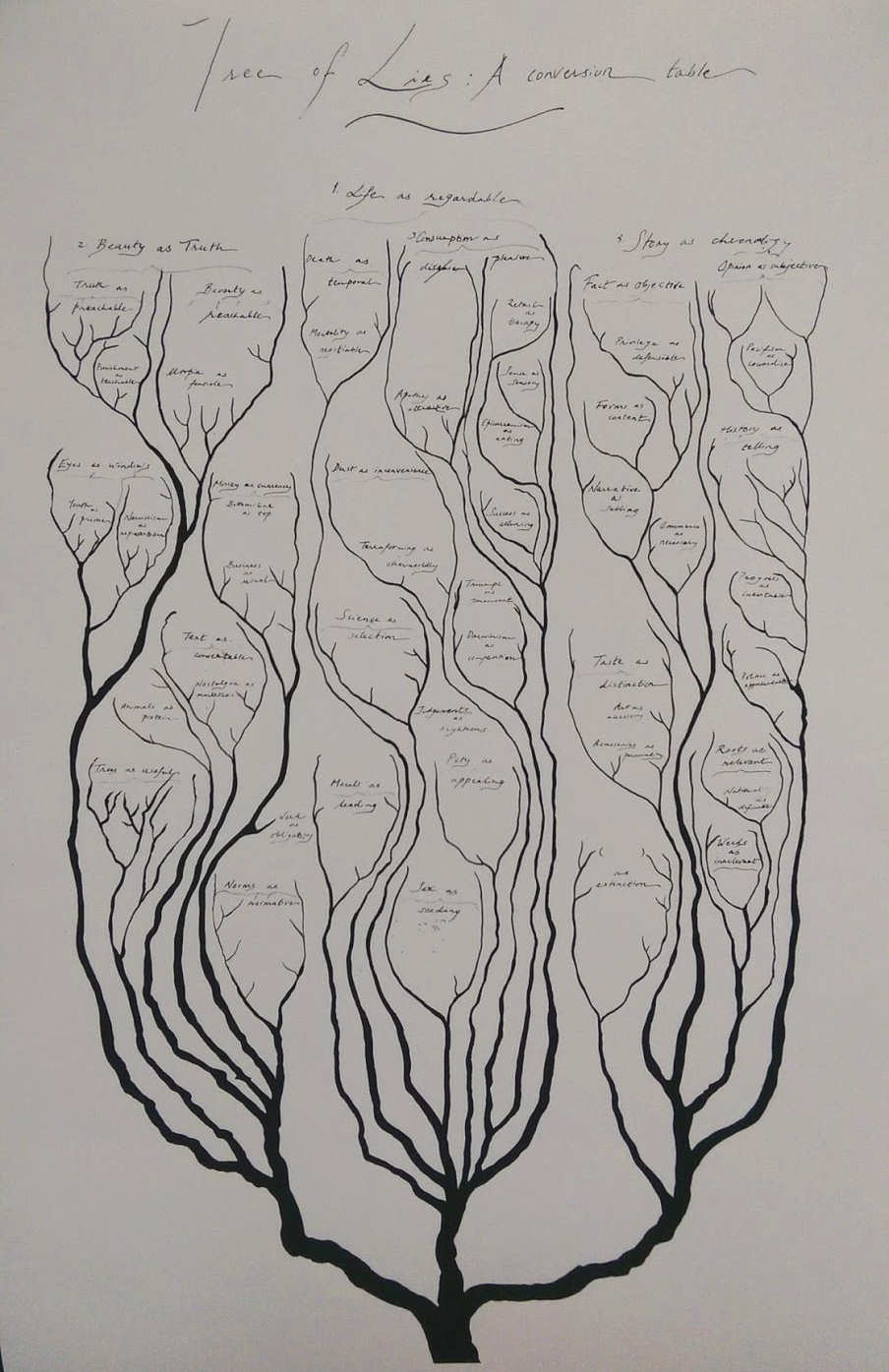

By Ekaterina Dobryakova Shubigi Rao, the Singapore-based artist whose works were presented at the OHBM 2018, grew up surrounded by science. As a child, she owned and was fascinated by rare books from the 17th-20th centuries that explored science and natural history. Neuroscience has always mesmerized her --- something she shares with brain mappers. Now Shubigi is a self-taught neuroscientist, with a neuroscience theory under her belt and art installations that often depict primordial ocean creatures with a complex central nervous system that are also reminiscent of sprouting dendrites and stained neurons. We reached out to Shubigi Rao to get a behind-the-scenes look at her artistic thought processes: Ekaterina Dobryakova (ED): You use many different mediums in your artwork and installations. Do you have a favorite technique and art form? Shubigi Rao (SR): This is a great question - the reason I have employed diverse media is because for me the idea or concept is paramount, and if necessary I will teach myself a new medium or discipline if the idea demands it. This has been a lot of fun, but challenging sometimes when working with deadlines, as I don't have the luxury of getting lost in the wonders of a new form or field of knowledge. Since my current 10-year project involves the study of cultural destruction - its history and also why our species has a hostile relationship with knowledge - I've re-trained myself as a solo film-maker, and have been travelling around the world to document sites, events, people and oral histories. In terms of artistic medium I've also loved drawing (such a primal impulse and one that predates verbal/written language) and printmaking, especially intaglio and etching, but my current love is definitely film-making. I've written a fair bit about the relationships between these media, and I enjoy reading the neuroscience behind the drawing impulse etc. ED: What was the most fascinating thing that you have learned during your studies of neuroscience? SR: Almost everything is fascinating to me - from the very first human articulation to know the working of the brain, to studies on sea-slugs. I even find the politics behind the institutionalization of R&D and corporatization of research, and the problematics of it all to be very urgent and important issues. I'm endlessly fascinated by current work in language acquisition in infants (and in other animals as well), and interspecies communication. To answer your question with a single example, I suppose it would be my first encounter with neuroscience, when, as a young adult, I wanted to understand how we see, especially how our brain processes visual information and can make 'sense' of abstract art for instance. I still remember my sense of amazement at the decoding from V1 to the inferotemporal cortices (I was reading Hubel and Weiss, I think). Also, Cajal's studies, of course, appealed to me greatly, (as I grew up reading books on natural history and the science of the natural world from sometimes outdated books of 18th-19th century naturalists and scientists), and I devoured his work, and biographies. ED: When I look at the works presented at OHBM 2018, I see ocean inhabitants such as the octopus and the jellyfish but these works also make me think about brain cells. What was your inspiration to create the works showcased at OHBM 2018? SR: I've been particularly interested in interspecies communication, and also the way anthropomorphism occurs in popular retellings of scientific breakthroughs. The octopus is of course a subject of much current study and interest for its unique neuroanatomy. I've also been enjoying how it has been reimagined in popular imagination - all the way from Viktor Hugo's infamous 'devilfish' in Toilers of the Sea, which created an indelible image of the octopus as monstrous, to its appearance at the famed Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace (London) in 1851. Our human imaginations (so essential to the artist) also make us invariably anthropomorphic and often unable to extrapolate from observed animal behavior without affixing human attributes. It's also why the life cycle of 'immortal' Turritopsis dohrnii has so seized public imagination. Invertebrates have often been classed as lower life forms, yet their neurological systems are amazing - the surprisingly complex nerve nets of siphonophores, their radial symmetry. I make my work ambiguous and open, to allow the brains of the viewer to fill in the blanks, rather than passively look at an image. I hope the viewer will enter it, get lost in it, reimagine or re-contextualize it. For OHBM, I mixed fact and fiction. I was inspired by the way the human brain attempts to understand 'alien' or radically different intelligences and neuroanatomy, and the way we confabulate those gaps. This is also because of my lifelong study of how we look at nature. I grew up in a forest - my parents left the city and took us to live in the jungles of northern India, where we learned how to 'read' interspecies communication between prey species, for instance, so we knew when a predator was on the move by the types of alarm calls of birds, monkeys, even insects. We developed a very intuitive appreciation for the lowliest of creatures, often disregarded in conservation efforts, for instance. It's only recently that the cause of bees have been taken up, yet one has to only read Karl von Frisch's brilliant work from 1973 on bee communication to see the incredibly complex nature of its dance and the way that communication can only occur because of a social agreement of its codes. So, the social aspects of information processing is what I unconsciously and intuitively imbibed growing up in the wild. All these elements feed back into the way I process disparate information, make connections, and interpret - which is what eventually led to my seeking out neuroscientific studies as a youngster, despite being disallowed from studying science at a higher level because of my gender. ED: One can say that, just as artists, researchers have to start with an idea, an inspiration, that subsequently culminates in writing of a publication or a work of art. Do you get ‘writer’s block’?

SR: Yes, I do, sometimes, but once I start I don't stop. My writer's block is often because of the sheer enormity of the subject and its associated bodies of knowledge, that I am paralyzed into being unable to decide where to begin. Of course, like most people, once I start then it's off to the races, and I work in a fever of hyper-focus to the exclusion of everything, often forgetting to eat. I recently finished 65000 words in under 10 days, after being paralyzed with indecision for 7 months. So, a very uneconomical way of working! ED: Many thanks Shubigi!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed