|

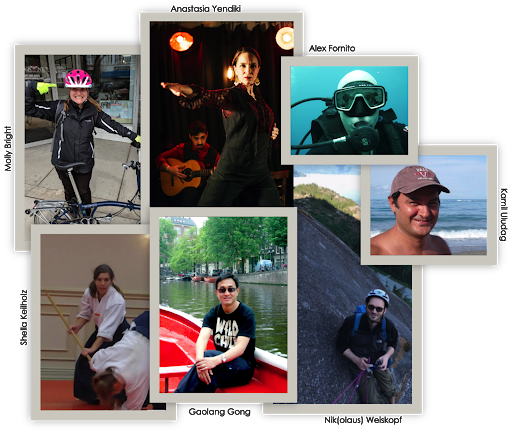

By Ilona Lipp and Jean Chen Edited by: Nils Muhlert In science, the term “work-life balance” may seem like a holy grail for some and a conundrum for others. Its easy matter-of-factness belies deep self-examination. Today’s research communities are larger and more competitive than ever with regard to permanent positions and funding, with the success rate for many grants being as low as 5%. For this reason many leave academia after finishing their PhDs (according to a recent report by the Royal Society). For those who choose to stay, the clock starts ticking from the very moment one starts a job, and the counting begins --- for grants, for journal articles, for trainees, for experience in international labs, etc. So who are the people that, despite everything seemingly being against the odds, persevere and manage to stand out in a world of stressed early-career researchers? Do they purposely dedicate their lives to science? Do they have a life outside of work? Are they even human? To find out, we talked to a diverse group of seven early-to-mid-career researchers, all highly successful for their career stage in terms of their funding situation, publication list and professional recognition (below, ordered by first name). We asked them how important work-life balance is to them and what strategies they take to achieve it, and have summarized their answers for you. Alex Fornito is Professor at the Turner Institute of Brain and Mental Health, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. Anastasia Yendiki is Assistant Professor at the Martinos Center in Massachusetts, USA. Gaolang Gong is Professor at the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, Beijing Normal University, China. Kamil Uludag is Associate Professor at Korean Institute for Basic Science/University of Toronto. Molly Bright is Assistant Professor at Northwestern University, USA. Nik(olaus) Weiskopf is Professor and Managing Director of the Max-Planck-Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany. Shella Keilholz is Associate Professor at Emory University/Georgia Tech, USA Let’s talk about “work-rest-of-life” balance instead!

First, we should agree on the terminology. Defining “work-life balance” in the research setting can be challenging. Our interviewees agreed that, as nicely phrased by Anastasia, “if it sits on the opposite side of a hyphen from the word ‘work’, then ’life’ has to mean any of the things you do that don’t contribute to improving your standing at work. Sleep is a solid example. Dancing flamenco is another.” Practically, the boundary is not always easy to draw. Shella proposes the term “work-rest-of-life” balance: “The term ‘work-life balance’ has always seemed a little inaccurate to me. My work is a big part of my life and I wouldn’t change that because I love what I do. It’s more like ‘work-rest-of-life’ balance”. Do we need a balance? Passion for what we do is undeniably important for academic success, however, as Alex points out, “sometimes the passion can blur the boundary between professional and personal life; science often feels more like a hobby than a job, and so it's easy for people to convince themselves to keep working longer hours.” Going deeper, he remarks that many of us in science tend to be conscientious and diligent high-achievers. However, he also understands how these very qualities, combined with pressure to compete for limited funding and resources “make a perfect recipe for an unbalanced life.” So, can a single-minded focus on work be unproductive? Alex thinks it may even be deeply damaging: “Drawing pleasure from activities outside of work, whether they are based on social relationships, sporting groups or hobbies, is an essential part of being a balanced, well-rounded person. It also ensures that your sense of self-worth and life satisfaction are not tied to any single thing, which is always a bad idea (especially in a field as fickle as science).” Kamil, who is a key figure in fMRI-physics research and a history enthusiast, tries to find time to keep up-to-date with his interest: “Life and work are not opposites but merely a distinction to divide my private life and profession.” Molly, the most junior scientist in our group, has achieved considerable success whilst developing her skills as a musician: “I have been fortunate to find orchestras to play in throughout my transitions from graduate, to postdoctoral, to faculty positions. Playing music is inherently a social activity, and gives me a parallel community to my research environment, as well as an active, enjoyable, and fulfilling evening that I must commit to at least once a week.” On the other hand, our interviewees emphasised the priority that should be given to relationships away from work. “My work-life balance is not only important for me and for my own sanity, but also for people I care about and who care about me.” mused Nik, “I think it is important to set your priorities right, some things simply always come before work, such as family and friends.” Molly echoed the importance of supportive friends and partners: “There is no substitute for a close relationship that acknowledges, supports and balances the unique challenges of academia”. How can a healthy work-life balance actually benefit your work -- The power of “distractions”! Many of us, especially junior researchers, may believe that dedicating time for non-work related activities will be a “distraction” and detrimental to one’s chances of publishing paper X or securing grant Y. However, our scientists all seem to agree that having activities outside of life is not procrastinating, instead it can help rather than hinder your productivity. A common theme was that time away from the office can give you a fresh perspective.“I don't believe I can work effectively for a long time without a ‘life’.” says Gaolang. Shella complemented this viewpoint with a practical example: “It’s useless to stare at my computer for 14 hours waiting for inspiration—it never comes. But while I’m out for a run, or returning library books on campus, or watching the kids at the park, then the ideas appear.” Nik offered similar experiences: “I have had many good ideas for work while doing something completely unrelated. In particular, doing sports helps my work by letting me clear my mind.” Kamil simply recognizes that when he’s had “enough research at some point in a day”, that he has to do something else. “I read novels and non-fiction books, watch movies or TV series, meet friends for dinner or some drinks… I feel more inspired, develop more scientific ideas and broader perspectives.” On top of these benefits, Gaolang adds that these “distractions” might help you get over humps in your research: “My family members are hugely supportive, and non-work activities with them can help me get rid of the frustration from work very effectively… I simply release myself back into ‘life’ if I feel I am not in the right mood/condition for ‘work’.” Knowing that successful brain mappers are actually human with quite a lot of life outside of work, can we learn their strategies for making it happen? Begin by knowing yourself! “Knowing oneself is the best way to win” --- this is derived from an old adage from Sun Tzu’s “the Art of War”, and is part of Gaolang’s wisdom in dealing with work-life challenges. “I don't believe people can really change themselves after reaching adulthood, so they need to really know who they are [in terms of] merits/weaknesses.” If you don’t know yourself by now, it’s not too late to start, and a good starting point, according to Nik, is to “ask yourself whether your current strategies are successful”. He adds that it’s fine to constantly change and update your strategy. After all, life is constantly changing. Molly gives us an example for how to do this “I’ve learned that I can use my commute to improve my day – I’m a committed bike-commuter here in Chicago, using my trusty folding bike that fits under my desk in the office. Driving would add stress to my day, and although I could get work done on a bus or train, I love how cycling clears my head so that I can be more focused at work.” We also asked our interviewees how they set themselves realistic goals. Gaolang answered: “When I set goals I aim to take advantage of my merits and avoid my weaknesses.” Anastasia went further, admitting that her goals are not always realistic, but that this suits her: “In the process of trying to meet my unrealistically high goals, I end up attaining some in-between goals, and I am starting to suspect that this may be OK.” Nik takes a more mixed approach, aiming high, building safety nets and being prepared for any outcome: “In terms of research, I love to have goals that are not necessarily realistic, but highly ambitious and risky, doing very fundamental research. But it’s equally important to have a more plannable and predictive line of research, with realistic goals and timelines.” Kamil thinks that the base of all ambition has to be excellent science. His strategy is to develop his goals naturally from everyday work: “I think reading outside of my own topics prevents that I get lost in details, develop tunnel vision and often gives me inspiration to do better science. I think far-reaching goals have to be broken down into individual goals, which are easier to reach.” Organisation is key! Effective time management is usually learned through experience -- but only if you know why you need it. Our scientists think that you cannot achieve “work-life balance” without organising your time well. A good starting point is to keep a “day timer” or diary. Shella reserves time in her diary for anything work-related she needs to do: ”When I get a paper to review, I’ll hold time on my calendar for it. When I’m writing a grant, I set aside certain times and avoid scheduling meetings then. Lately I’ve found that it even helps to block time for reading papers and brainstorming, just so that the inevitable meetings, seminars, and paperwork don’t crowd out other important things.”. Alex has a similar and strict approach to time-management: “I plan my meetings for specific days, answer emails within certain time windows, and I don't use alerts on my phone. I also try to draw strict boundaries between family time and work time (e.g., I very rarely do any work on weekends).” This didn’t come naturally, and he admits: “At first, there can be some anxiety associated with drawing such boundaries, but over time you realise that the sky will not cave in, and that it actually does not make that much difference to your productivity. You will feel happier and more relaxed though.” One of Kamil’s tricks is to reserve times for activities beyond my work and not to respond to emails during these times. “I also usually set-up meetings with colleagues and students in the afternoon to keep the mornings free for my own research and writing.” He admits to deviating from his routine, but that’s part of the learning: “When I work too much in the weekends, I feel guilty that I neglect my other interests, which helps me to readjust to my balance.” Anastasia learned that both the work and non-work activities need to be well planned: “Part of my strategy is to accept the fact that things will get off balance at times, and to plan for it. There will be times when I will be working 22 hours a day because of a deadline. Knowing that, I make a point of creating other times and spaces that allow me to let the balance tip the other way. This has to be planned in advance, and for me it may involve traveling, spending time with people, or spending time by myself in a dance studio. My goal is not to experience it as a failure when the balance is off, whether it is because of too much work or too much life, but to accept this as the nature of my balance.” To keep a healthy work-life balance, Molly leverages the usually quite flexible working times that came with an academic job. “I often have times (e.g., grant deadlines, ISMRM submission deadlines) when I do need to stay in the office until late or bring my work home with me on the weekend,” she explains, “but I remain fairly nimble to respond to whatever else is happening in my life, whether it be a family emergency, family celebration, important event, or simply a much-needed break. Knowing that I am generally free to make time for these aspects of my personal life makes it far easier to work hard when it’s most needed.” Nik points out how important time management becomes once you manage other people: “The more senior you become the less time you will have for certain things, such as immersing yourself in a particular topic. It also becomes more difficult to put things on the backburner, so you need strategies to save time. The more efficiently you manage your group, the easier it is to prioritise your time within and outside work. On the other hand, when something in the team does not work efficiently, you yourself cannot compensate for it all.” He cautions that this is something people often miss when transitioning from an individual researcher to a group leader. The role of family in work-life balance? To Anastasia, successful researchers don’t need to be single-minded: “It is a detriment to the field to discourage individuals who are driven and intelligent but who do not fit that image.” She adds, however, “Having a family is an example in the grey area, as it is known to make certain people be perceived as less committed to work and others as more mature and ready for positions of responsibility.” Alex and Shella both have young children, and spend most of their time outside of work with their families. Shella noted that despite the additional responsibility, it increased her productivity: ”I was amazed at how productive I became at work after my first daughter was born. Knowing that I had a limited time to get things done really helped me to be efficient. I cut my 10-12 hour days down to 8 without really losing any productivity. I never thought that I was unproductive before, but the time pressure really helped me to prioritize the important things. Before, I might have spent half a day tweaking a single paragraph.” For Shella, who runs a prolific animal-MRI lab, having a supportive partner is also key: “It makes the balancing act a family matter rather than something I have to handle on my own. We hire help to keep the house clean and the lawn mowed to give us more time with the kids, and we trade off weeknights so that we can each go running or train at the dojo.” Gaolang takes a more laissez-faire approach :”Sometimes I am not the only decision maker at all; you have to follow your wife and daughters' command to get into family time.” How to have it all: advice for junior scientists Alex Fornito certainly thinks you can have it all, and suggests starting small: “Have at least one thing that you do which is not work-related. It’s critical for students to schedule some personal time each day - whether that’s for exercise, meditation, practising an instrument, or whatever. Ideally, this would be complemented by some other activity with other people (e.g., sporting team, musical band, hobby group etc) throughout the week.” He adds: “make sure that you have at least one day per week on which you don’t do any work. You may have busy periods where you can't maintain this schedule, but you should try to be as disciplined as possible because it pays off in the long run.” If you want to have it all, finding a supportive work environment is a good starting point. Nik, in his capacity as Managing Director, thinks that “being in a managing position, it is also important to provide the right environment for your team members to have a good work-life balance. For example by making sure people take their holidays and by keeping an eye on their stress levels.” Nik also emphasizes the importance of having a supportive institute “Providing family support such as day care for children, and offering a program for activities that promote a healthy lifestyle in general can really make a difference.” Gaolang considers his job very cool, but advises getting ready for both good and bad surprises on the way: “My specific recommendations are, #1, work hard on research but take time to enjoy your life, #2, keep pushing yourself forward and make solid progress step-by-step, #3, Keep the big picture of your research in your mind and occasionally think about it, but not always!” Finally, as Anastasia points out: “It’s important to remember that being able to speak of work-life balance is a privilege, as there is a large percentage of humanity that has to work under brutal conditions only to survive.” Postamble Science is competitive and we will all have ups and downs. In the process, let’s not forget that we’re first and foremost human beings, and that our “life” away from the lab will be our anchor through the good and the bad in academia. Let’s also not forget that we’re privileged to be doing something we love as a job, so we might as well aim to stay mentally and physically healthy while doing it. With this, we want to wish everyone a productive 2019 and a healthy work-rest-of-life balance.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed