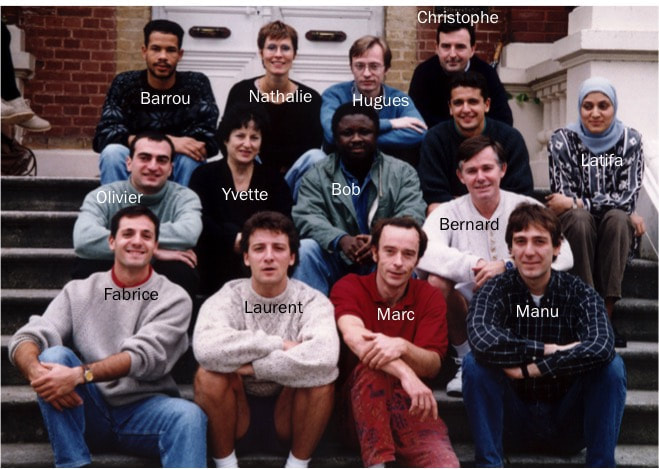

Bernard Mazoyer Bernard Mazoyer By Nils Muhlert Bernard Mazoyer, Professor of Radiology & Medical Imaging at Bordeaux University Hospital, has been at the forefront of the human brain mapping community for thirty years. In 1989, Bernard, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer and Marc Joliot founded the functional imaging group (GIN-IRM), the first neuroimaging group in France. As a founder member of OHBM --- indeed, organising what was to become its first meeting in Paris --- Bernard has seen the organisation grow from hundreds of members to many thousands. Here we find out about his background, and his views on why OHBM may now be ready to become a society: Nils Muhlert (NM): Can you tell us about your route to neuroimaging? Bernard Mazoyer (BM): My initial background was in mathematics, which I completed with a PhD in biostatistics. I taught maths for a few years but I was more attracted by maths applied to biology and medicine. So I decided to go to medical school and started doing research in a medical nuclear imaging department. My first project in 1979 evaluated the paths through which blood moves from outside to within the brain by measuring the transit time of a radionuclide injected in the carotid artery using brain images provided by a gamma camera. Soon after my MD, I spent 2 years as a postdoc at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory where I worked on PET and MR advanced instrumentation and image processing. When I returned to France in 1986, Marcus Raichle and his colleagues from Saint-Louis had invented the PET O15 water brain activation mapping method and I was hired by the Atomic Energy Commission to implement and develop applications of this method. With my colleagues from CEA, namely my wife Nathalie Tzourio and Marc Joliot, we founded the GIN, the first research unit in France devoted to human brain mapping (HBM). Thirty years later we are still working together in the HBM domain. NM: What do you feel have been the real breakthrough findings within GIN-IRM? BM: Hard to answer that question! The GIN has been in the field since 1989 and has contributed over 200 articles. Besides, as with several other pioneer research groups in the HBM field, over its lifetime the GIN has gathered researchers from a variety of fields, from neuroimaging methods to cognitive (language, attention, mental imagery) and clinical (schizophrenia, Parkinson disease, Alzheimer disease) neuroscience. If I were to select the one study that I believe has had the highest impact on the field, I would certainly put forward the AAL: the atlas of anatomical ROIs. In the mid-1990’s the brain mapping community had largely adopted the stereotactic averaging approach, but there was no standard for labeling activation. On our side, we were interested in individual variability and thus very eager to match structural MR with PET. The AAL was conceived by Nathalie to solve these issues. Building upon a longstanding collaboration with the French neuroanatomist Georges Salamon, Nathalie designed an atlas of ROI’s having sulcal limits, literally spending days tracing the sulci and gyri on Louis Collins’ brain MRI slices. This quite tedious work provided the community with the reference anatomical labeling method it needed. Amazingly, in 15 years, AAL has reached over 5,000 citations and has been adopted not only by the HBM community but also by many clinicians. NM: You’ve been involved in OHBM since the very beginning. Initially, what were you looking to achieve, or what particular interests did you want to highlight, through OHBM?

BM: The main goal of the first OHBM meeting in Paris in 1995 was to gather together the different communities involved in human cognitive neuroimaging. In the early 1990’s, PET was in its golden age thanks to the O15-water blood flow mapping, functional MRI was just born, MEG was being developed and EEG-cartography was just starting. Cognitive process mapping was the common denominator for all, but was not clearly identified as a field of research of its own. As a matter of fact, there were no meetings or professional societies where these different communities could meet. In particular, methodological issues were very important but there was rarely an open forum for discussions. So Paris was really designed as a place for exchange between neuroimaging communities with the long-term prospect of gathering all communities within a common scientific society. NM: How do you feel the organization has changed over the years? Do you feel Alan Evan’s famous OHBM helmet can stay safely locked away in his office, or have there been times when the debates may have required it? BM: The main change that has happened over the past 20 years is certainly the sustained development of OHBM, in terms of membership, meeting attendees, and spectrum of activities. Membership has reached 2,000, and while 900 people showed up in Paris 1995, an average of 2,500 have attended the recent OHBM meetings. More importantly, we started as an organization, i.e. a structure focused on setting up an annual meeting. Today, my personal view is that we are now a society, i.e. a group of individuals, with a large spectrum of shared activities besides the annual meeting. To name a few, we have regional chapters, special interest groups, committees on gender and diversity, multimodality, education, career, and we are developing relationships with societies’ sharing some of our goals. This development has been progressing over the past 20 years and came about as the result of demands from the OHBM community. I am not saying that some strategic options and their implementation did not raise concerns and debates. But, apart from that very hot first business session in 1996 in Boston, this development has been discussed and conducted in a constructive and peaceful atmosphere. So yes, I consider it very unlikely that Alan’s helmet will ever be used again. NM: We’ve recently found out that OHBM 2018 will now be held in Singapore. How did this decision come about – and what can we look forward to in the Lion City? BM: Due to the continuous degradation of the relationships between North Korea and other countries and repeated demonstration of military threats, both OHBM office and council members have received since June numerous messages of concern from OHBM members and sponsors about holding the 2018 meeting in Seoul. According to our bylaws, only the council can decide on the annual meeting location, and discussions between council members have been under way for several weeks. In September, the decision to move the meeting away from Seoul was approved by a very large majority of Council members. But it has been a difficult decision to take for every one of us because we were all well aware of, and very grateful for, the extraordinary job done by our Korean colleagues within the Seoul local organizing committee. However, we were also conscious that the meeting had to be moved away from Korea in order to give everyone a chance to attend next year’s meeting. This was the basis for our decision. The choice of Singapore was less difficult, first because we wanted the meeting to stay in Asia, and second because Singapore was previously shortlisted as a potential host for OHBM2018. So, with the help of our Singapore colleagues, who were very responsive in forming a local committee, we all expect to have a great meeting in Singapore despite the overlap with the ISMRM meeting. As always, it will be attendees who make the OHBM 2018 meeting a big success. NM: As OHBM Chair, what do you hope to achieve during your tenure? BM: My first hope is to successfully lead the building of the new OHBM strategic plan for the next 3 years. It is Karen Berman who pushed the idea of having a strategic plan and it is under her leadership that the first OHBM strategic plan (2015-2017) was conceived. This plan has been instrumental in implementing fundamental elements of OHBM functioning and development. To name a few, gender and diversity, the increased role of students and interactions with other societies have been essential and successful components of the first strategic plan. In the new plan, I hope we will include among others very important topics such as developing HBM science in countries with limited resources, promoting the role of brain mapping in education and healthcare, and open science. My second hope is that OHBM becomes a Society. My view is that an Organization is a structure set up with a defined goal whereas a Society is a gathering of individuals sharing common interests and values. I believe that the past history of OHBM and its current large spectrum of activities both advocate for becoming a Society. My third specific hope is to have multimodality increase its place and visibility within OHBM. We need to be more open to methods other than MR and to be at the forefront of combining brain signals. But we need also to promote multimodality in a broader sense, namely combining neuroimaging signals with signals obtained at other scales, from genes to behavior, as well as in species other than humans. This, I think, is one of the main aims of OHBM future development. NM: Last, what do you see as the main challenges facing OHBM over the next 5-10 years? BM: OHBM is still a young “Society” and its steady development over the past 20 years has been fueled thanks to the advent and development of in vivo HBM tools and related neuroscience research at the systems level. This field of research is very rapidly expanding. In my opinion, the major challenge facing OHBM in the future will be to maintain the coherence of the HBM community while attracting scientists from other domains that are now essential for understanding brain systems. Maintaining the coherence of the HBM community is a challenge by itself, as the risk of split from groups of people with insufficiently represented special interests is very high, given the size of OHBM. Meanwhile, attracting scientists from other domains is a challenge as well, as it will require giving them the space they need within OHBM. NM: Many thanks Bernard - we look forward to OHBM 2018 in Singapore!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed