|

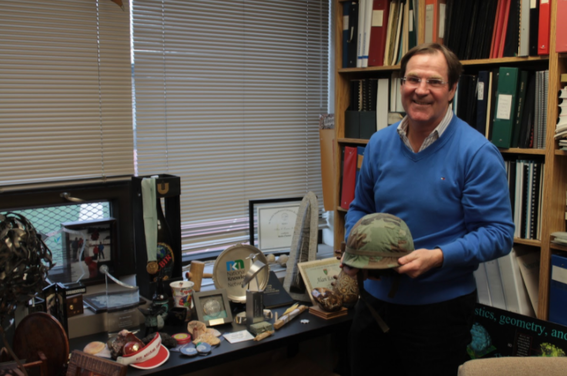

BY NIKOLA STIKOV Alan Evans is a natural storyteller. He has been with the OHBM since its very beginning, and he has the stories to show for it. We spent a pleasant afternoon in his office at the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI), talking about the turbulent early days of the organization, peeling off the hidden layers of brain imaging, and wading through his memorabilia collection, which he affectionately calls ‘the little shop of horrors’. The central place in this collection is reserved for an old military helmet, which is only one of the many hats that Alan has worn for the society. Nikola Stikov (NS): What is the story behind the helmet? Alan Evans (AE): Well, throughout the 80s my contemporaries and I were going to five, six, seven different conferences in a given year, each covering different aspects of what interested us. Soon it became clear that we wanted our own community, so Bernard Mazoyer volunteered to organize the first OHBM meeting in Paris. Back then there was this big debate on whether we should call ourselves a society or an organization, because some people wanted to keep us paired with other existing societies, such as CBFM (Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism). This debate rumbled on from the very first meeting, and at the second meeting in Boston in 1996 I was asked to be a moderator of the town hall. So that afternoon I went to the local military surplus store, I bought a helmet and put it under the table. And then when the town hall started I said ‘I understand that today will be another chapter of what has become a contentious discussion, so I have come prepared.’ Then I put the helmet on and the whole auditorium erupted in laughter, diffusing the tension. Then I put the helmet back on the floor and forgot about it. But the story doesn’t end here.

NS: So what brought you to the MNI? AE: I was one of two physicists working on the development of a PET scanner, a commercial version of the PET scanner that was built here at the MNI. The original PET scanners were designed by Chris Thompson at the Montreal Neurological Institute, and AECL took his prototype and redesigned it for commercial purposes. So I did a lot of “suitcase physics”, running between AECL in Ottawa, the Chalk River nuclear facility and the MNI, where I worked with Chris Thompson, the developer of the bismuth germanate crystal based PET scanner that replaced sodium iodide PET scanners. Bill Feindel was director of the MNI, so when the program folded in 1984 because AECL realized PET scanners were not commercially viable at that time, Feindel asked me to come to the newly established McConnell Brain Imaging Centre (BIC) at the MNI, which was the world’s first dedicated brain imaging research environment. NS: Which you eventually got to lead as its director… AE: Yes, when I took over as director in the 90s I became interested in brain mapping, first with PET activation studies, atlases, and subsequently throughout the 90s more and more with fMRI. I was lucky that I was able to find Keith Worsley, who was a dear friend and partner in crime for many years. The one thing I remember vividly about those days was the bunker, a little room deep in the bowels of the BIC. There were many weekly meetings with Keith, Sean Marrett and Peter Neelin, very smart people who were permanent staff and comprised what I like to call the hidden layers at the BIC. This pattern of hiring a cadre of permanent highly-qualified scientific staff in addition to transient PhD students and fellows was critical to the continued growth of the lab.

NS: Can you tell us a little about your lab today?

AE: Currently I have about 65 people in the lab. About half of them are the scientists who are asking the biological questions, and the other half are the geeks who build the computing and neuroinformatics infrastructure. The challenge is to make sure these people stay together and have a common mission. The lab operates at three levels. First is the IT infrastructure and things like CBRAIN and LORIS. Second is developing algorithms and analytical methods to explore connectivity, and the third is applications of those methods to specific patient cohorts. The two major domains are developmental disorders, autism in particular, and neurodegeneration, particularly Alzheimer’s disease. One of the high points of our recent activity has been the work of post-doc Yasser Iturria-Medina, who has been developing causal models of amyloid propagation in Alzheimer’s using a number of different imaging metrics. Now we are working on generalizing this machinery so as to apply it in development, using the same underlying modelling principles but applied to different imaging metrics. I believe It is important to preserve the general approach as far as possible before it is customized for different applications, but you need a methodological and IT critical mass to support this approach. NS: What do you think are the most burning questions in neuroimaging today? AE: Over the years my research has become more involved with connectivity, both structural and functional. Historically, imaging had spent over 20 years confirming what it was possible to do with more invasive methods by identifying focal areas of response to stimulus. There were people who were not convinced that imaging added anything new beyond, for instance, single unit recording. At the turn of the millennium, however, it became evident that imaging can do things other methods cannot, i.e. conduct a whole brain non-invasive survey of brain structure and function. So we could then start to explore the interaction between different parts of the brain, its underlying systems circuitry, over time. This opened up a whole new frontier to examine subtle aspects of brain connectivity in normal brain and in distributed disorders of neurodevelopment and aging. Scientifically, I think that our field is getting very exciting, if overwhelming, with the consolidation of neuroimaging with other forms of brain data. We should be looking to integrate other forms of information, such as behavior and genetics into the multi-modal characterization of brain states. Some argue that we will lose focus if we do that, but I believe that the way we will understand the brain is by incorporating all this information, along with the computation and big data analytics machinery to combine all this information in predictive models. I think the next 10-20 years will be a golden era for the organization. NS: Which brings us back to the OHBM and its role as a leader in the field of neuroimaging. What can we expect from the annual meeting in Vancouver? AE: I feel that in Geneva we came of age, so we are more realistically functioning now as a society. We are broadening our pallet of activities, be it through international chapters or through special interest groups such as the hackathons. I feel like the geeks are the lifeblood of the society, so we can expect more organizational practices, white papers on best practices, as we have seen with the COBIDAS report. NS: Is there one topic that you are proud to bring to the table as chair? AE: Well, one of the questions that is going to come up in Vancouver is the question of diversity. I am both delighted and nervous about this, as we recently launched a diversity task force on my watch and this has revealed some schisms between people who want to prescribe solutions and those who want to see this process evolve organically. It is not my place to voice a personal opinion, but I look forward to the discussions at the upcoming town hall meeting. NS: There are many aspects to diversity, gender and geography being two of the more obvious ones. How do you feel about the recent changes in US immigration policy that will prevent some scientists from attending the annual meeting? AE: I am very much an internationalist, so I find it unacceptable that people would be prevented from attending meetings based on their nationalities. We as a scientific community have to be on record that we reject identity politics. My lab and OHBM on a bigger scale are excellent examples of how we are being enriched by the international exchange of ideas.

3 Comments

Mike Chee

6/25/2017 06:00:21 am

Oops - Nikola - You should be credited! I guess the comms initiative was started by Randy but you did the heavy lifting here. Great job I really love reading bios.

Reply

Nikola Stikov

6/25/2017 12:57:05 pm

Thank you Mike, I appreciate the enthusiasm! It is truly a team effort, and we could always use more volunteers:)

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed