|

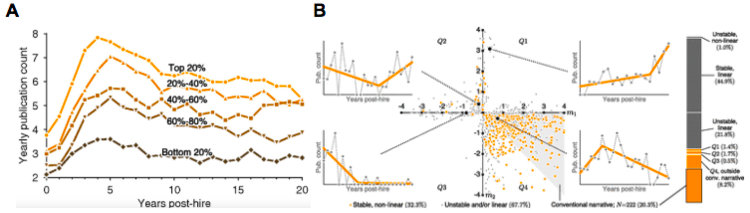

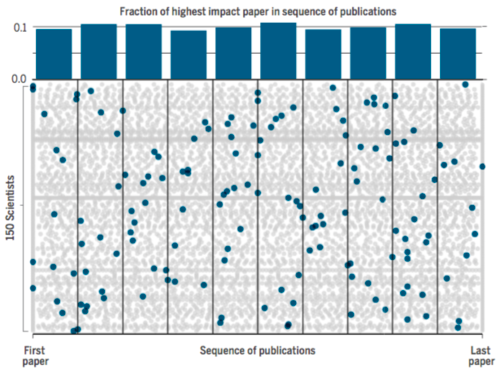

By Ayaka Ando & Natalia Z. Bielczyk, OHBM Student and Postdoc Special Interest Group, Edited by AmanPreet Badhwar Christmas is just around the corner and the deadline for the OHBM annual meeting abstract submission is fast approaching! The OHBM Student and Postdoc Special Interest Group (SP-SIG) also had a busy 2018 organizing the Secrets behind Success symposium in Singapore, launching the third round of the International Online Mentoring Programme (attracting an additional ~150 participants), and launching the new SP-SIG blog. Considering a new year is upon us soon, we wanted to share with you some insights we have gained by interviewing researchers in academia and industry. In this blog, we present a collection of interesting insights from our 2018 interview series. For the full interviews, please visit our SP-SIG blog. Leaving academia is not a failure Leaving academia as a conscious career choice is often seen as a failure (Kruger, 2018). However, this is what Dr Anita Bowles, the Head of Academic Research & Learner Studies at Rosetta Stone in San Jose, California, had to say about her experience: “People often feel like a failure if they are thinking about leaving academia. I talk to a lot of graduate students in this situation and I understand their concerns, because I felt the same way. I would like to tell these students that this is not the case at all once you are on the other side of the decision. You can do valuable and satisfying things outside academia, including research that can be applied to help people. And if you feel like trying, just go for it.” How to find jobs in industry If one decides to leave academia, the first impulse is to browse through job listings. We, however, found that our interviewees had varied approaches. Dr Anita Bowles says: “I found out about Rosetta Stone through networking: I knew someone else who was employed by the company and who also had moved from academia to industry. I am glad that it turned out this way for me, as what I am doing now has a lot of overlap with my past research, and I am passionate about this topic.” Dr Ricarda Braukmann, a recent PhD graduate, and currently a Program Leader for Social Sciences at Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS) told us: “As I was already passionate about open science and knew of the work DANS was doing, I was proactive and contacted them explaining my wish to gain experience outside academia. I was very lucky, as I indeed got the chance to work for DANS during a four months part-time internship in my final, fourth year of the PhD. The internship was the starting point of the job I have now, which DANS offered me after I finished my PhD.” Natalia Nowakowska, a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam and a freelance copy- and content-writer, also started her job as a freelancer by networking: “How did I start freelancing? In a way, it was also a lucky strike - I met a person in a bar who was leading a course on how to become a freelancer. I joined the course and got some practical instructions on how to start and find my own place in this space.” Every career path is different No matter how much we try not to, we sometimes still compare our career trajectories with our peers. However, from Dr Aaron Clauset, an Associate Professor of Computer Science at the University of Colorado at Boulder and in the BioFrontiers Institute, we learned that career trajectories in science are highly nonlinear. In his research Aaron and colleagues analyzed career paths of thousands of computer science professors at US and Canadian universities (Way et al., 2017, Clauset et al., 2017). What they found was that the conventional research trajectory of a rapid rise in productivity to an early peak, followed by a slow decline, only emerges after averaging the individual trajectories of large groups of scientists. Even though the average number of papers per person per year is higher in highly prestigious institutions than in other institutions, the shape of this average trajectory is independent from the prestige of the affiliated institution. However, the average pattern conceals high inter-individual variability in the career trajectories to the extent that only one in every three faculty members follow the average trajectory (Fig. 1).  Fig 1. The average trajectory versus inter-individual variability in the trajectories; a reprint from Way et al. (2017). (A) Average publication count follows conventional narrative across prestige, with the division into 5 groups of affiliations on the basis of the prestige. (B) In fact, there are four different types of trajectories, and most of the subjects do not follow this averaged, conventional trajectory. Research conducted in a group of 2,300 computer scientists from the U.S. and Canada. Furthermore, related work on citation to papers by physicists, carried out by Dr. Sinatra, one of Clauset’s collaborators and colleagues, revealed that groundbreaking discoveries seem to be equally likely at each career stage (Fig. 2, Sinatra et al., 2016). The results from these studies are very optimistic - in a sense that there is not just one canonical way of pursuing a career in academia, and that success can come at every ‘academic age’.

Start your own institute! Lastly, what do you do when you know deep inside that you should pursue a career in research, but the whole universe tries to prove you otherwise? We interviewed Jeff Hawkins, the founder of Redwood Neuroscience Institute & Numenta Inc., who finished his official research training with a BSc from Cornell University in 1979. Since then, Jeff never successfully accomplished a PhD because of constant rejections of his ideas that were ahead of his time. So, Jeff developed an impressive career in mobile computing in the Silicon Valley instead, where he established Palm and Handspring, two mobile computing companies. However, his thoughts have always circled around science. Today, Jeff leads his own research institute, Redwood. Recently, he gave a keynote lecture at the Open Day of the prestigious Human Brain Project summit in Maastricht, where he introduced his theory of grid cells in neocortex (a.k.a. a Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence) as the framework for cortical computation. He is very modest about his achievements, and, when asked about how he managed to create his own institute, Jeff answered: “It was easier than you imagine. The idea came from several neuroscientist friends of my mine who said the field of neuroscience needs cortical theory. They encouraged me to start an institute. I agreed only on the condition that they help me, and they did. There were a number of scientists who, like me, wanted to work on cortical theory, so they signed up.” Easy, right? :) If you would like to get involved in the SP-SIG activities, give us an interview or perform an interview that can be featured on our website, please contact us! Also, stay tuned for the roll-out of our next big project early next year! We are going to launch an open initiative, where any OHBM member is welcome to help us shape a set of guidelines (in a manuscript format) on effective self-management for early career researchers. We hope to meet you in this project!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed