|

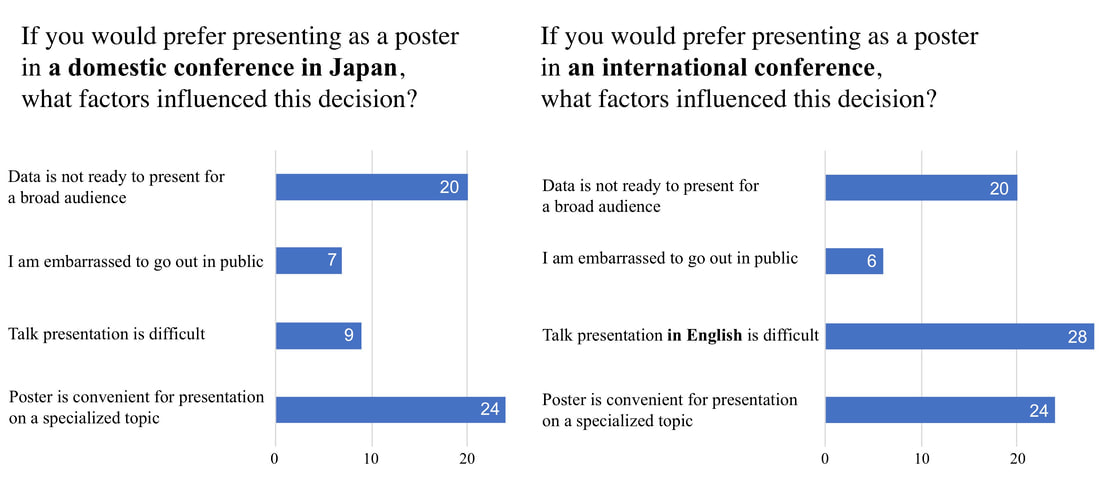

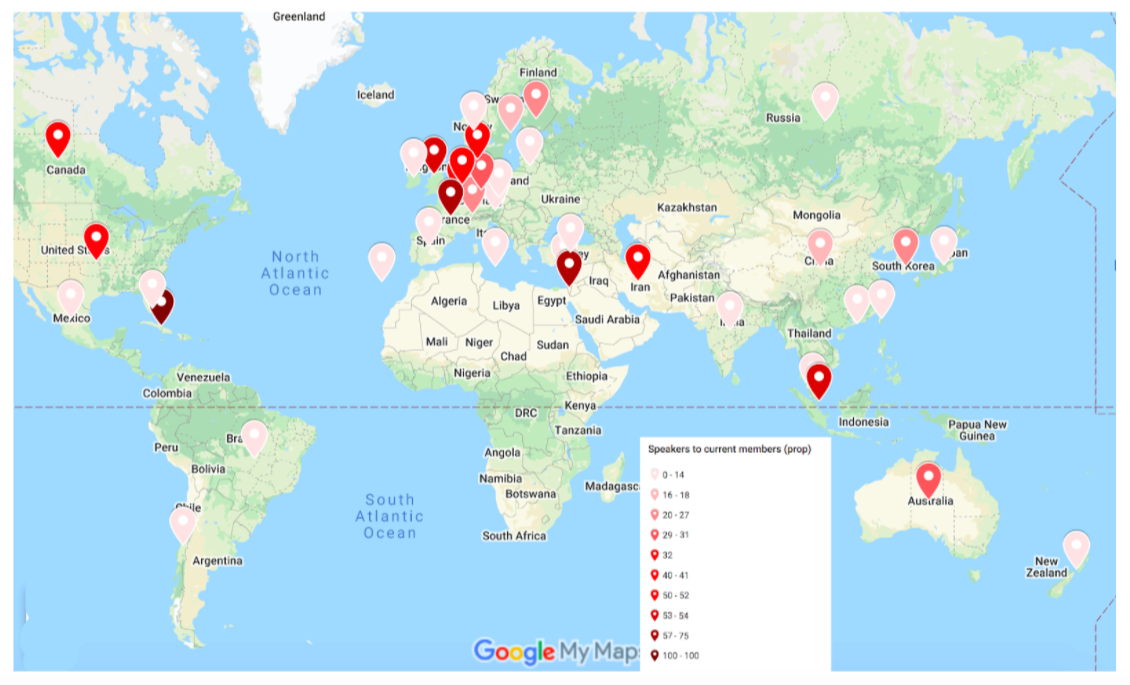

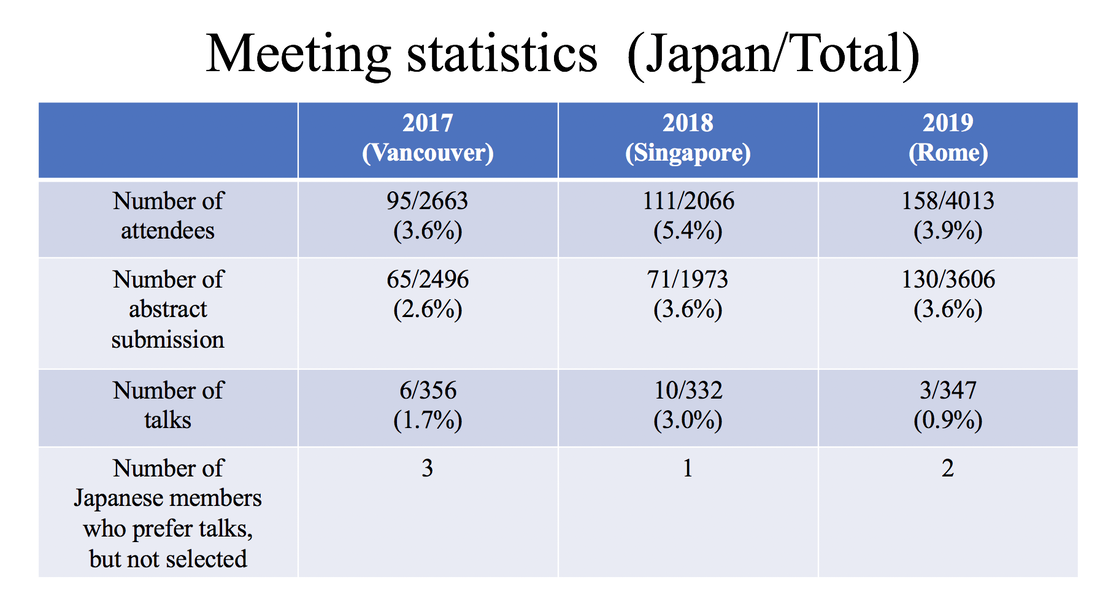

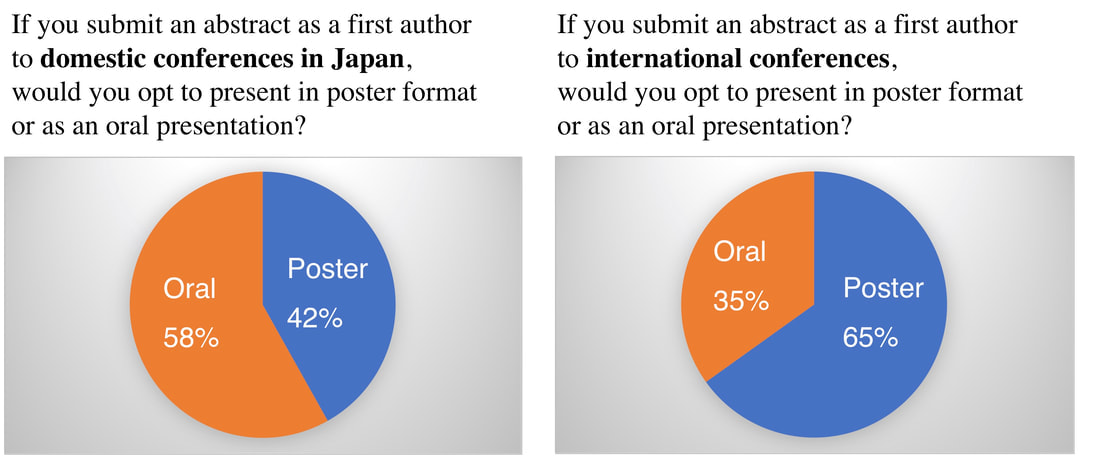

Guest post by Hiromasa Takemura International diversity is essential for organizations like OHBM. Through my experiences attending recent OHBM Annual Meetings, I have found myself asking why so few researchers from Japan have visible roles. To find out whether this was indeed the case, and possibly why, I worked with the OHBM Executive Staff, Diversity & Inclusivity Committee, and Communications Committee to analyse membership and attendance data from the annual meetings. By collecting and analysing this demographic data we can gain insight into why some countries (in this case Japan given my background, but the findings may extend to others) may be underrepresented at OHBM. Japan is the 11th most populous country in the world, with an estimated population of 126 million (m) people in 2020. For comparison, Mexico has the most similar population with 128m people and Germany, Europe’s most populous country, has 83m. Japan has, over the years, substantially contributed to the OHBM community: for instance, the 2002 Annual Meeting was held at Sendai, Japan and Dr. Kang Cheng, a pioneer of high-resolution fMRI studies at a founding lab for RIKEN's Brain Science Institute, is heavily involved in organization of OHBM meetings. To get a picture of recent involvement of researchers from Japan, we examined data summarizing attendance and presentations at the OHBM Annual Meeting between 2017-2019 (Table 1). We defined Japanese members as those affiliated with Japanese institutions. Using this definition we found that Japanese members comprised 3.6%, 5.4% and 3.9% of all attendees for 2017, 2018, and 2019 respectively, with the fluctuation reflecting the location of the annual meeting (OHBM 2018 was held in Singapore). We found a lower proportion of abstracts submitted by Japanese members: 2.6%, 3.6%, and 3.6% of the total number of abstracts for each of these years. We then examined the proportion of Japanese members giving oral presentations. These numbers included both regular oral sessions and symposia. The proportion was 1.7%, 3.0%, and 0.9% for 2017, 2018, and 2019 respectively. The low number at the 2019 Annual Meeting was striking, given the proportion of attendees and abstract submissions. To determine potential contributors to these statistics, we examined the number of Japanese members who selected “talk preferred” at abstract submission, but were not accepted for talk presentations. Surprisingly, these numbers were very small: 3, 1, and 2 for 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively. A major reason for underrepresentation of Japanese members at the OHBM meeting appeared to be a reluctance to present data in the form of a talk. It is true that certain types of presentations work better as posters than talks, but we wanted to find out why so few researchers from Japan opted for oral presentations. We wanted to find out why the community would miss opportunities to highlight and benefit from their work. Why do Japanese members hesitate to give talks at the OHBM annual meeting? To find out, we surveyed 86 Japanese scientists working in human brain mapping (Figure 1). First, we asked whether they would choose oral or poster presentations at domestic conferences: 58% answered “oral”. Then we asked whether they prefer oral or poster presentations at international conferences. In this case, only 35% answered “oral”. The trend to favor posters in international conferences was common across both junior and senior scientists. Next, we asked why they would opt for a poster presentation (Figure 2). For domestic conferences, researchers chose poster presentations when the topics were specialized, or the data wasn’t ready to present to a broad audience. For international conferences, 32.6% of respondents were dissuaded due to the challenge of presenting in English. Indeed, for Japanese researchers the most common deterrent for oral presentations at international conferences like OHBM was the language barrier.  Figure 2. Survey on the reason for choosing a poster presentation for a domestic (left) and an international conference (right). Multiple choices were allowed for this question. While there are common reasons between a domestic and an international conference, people raised a difficulty in English presentation as a reason to prefer poster presentation in international conferences. The challenge of presenting in English is not unique to Japanese members of OHBM. Instead, this case study serves to demonstrate the extent to which language barriers can limit scientific communication. It is, therefore, worth considering ways to organize an international conference that help enable non-native English speakers. There are several actions we can take as a community. First, we could promote and encourage junior Japanese members (and other non-native English speakers) to apply for oral presentations, symposia proposals and educational courses. My own experience speaking at the 2019 Annual Meeting greatly increased my enthusiasm and experience of the conference (see photo below). Second, as an international community, we can promote a friendly, open-minded environment for scientific presentations and debates across members, irrespective of their English proficiency. I appreciate that OHBM has made a clear Code of Conduct prohibiting harassment based on the accent of speakers. Since I believe that OHBM members are mutually respectful, I hope that non-native English speakers feel able to discuss their scientific work and ask questions during annual meetings. Third, we can devise conference formats that reduce language barriers. OHBM 2020 was a virtual event. This allowed members to communicate using live chat features that will be much less affected by spoken language proficiency. OHBM 2021 will now also be virtual, so we have time to consider further digital features to aid communication. Looking forward to the return of physical conferences, we can use features like mobile apps to ask questions, as we did at OHBM 2019. There may be no single solution, but we can benefit from technologies tested in virtual formats in future physical conferences to encourage broader active participation in OHBM meetings. We could ensure that new scientific advances are communicated widely, and not hindered by the lingua franca. Finally, it is worth restating that these issues are likely not specific to Japanese members. We hope that by shining a light on the challenges faced by my local community, we can increase accessibility for OHBM members from a variety of non-English speaking countries around the world. ---- Addendum (from the Diversity & Inclusivity Committee) To examine the breadth of underrepresentation, the Diversity & Inclusivity Committee examined the geographical distribution of speakers at OHBM 2020. We calculated the number of speakers (at regular oral sessions and symposia) as a proportion of current OHBM members (see figure below).  Our findings paint a complex picture: most Asian countries are certainly underrepresented but researchers from central European countries, including non-native English speakers, are well represented. However, the Romance or West Germanic languages of these latter countries share typology with English, and so are considered by the Foreign Service Institute to be easier for an English speaker to learn. In contrast, Japanese, Arabic, Cantonese and Mandarin are considered to be ‘exceptionally difficult’ for English speakers to learn, and vice versa. Other factors likely influence whether researchers submit abstracts as oral presentations. For example, Spain and Mexico, despite their Romance language, had relatively few speakers. Historical ties to OHBM from individual labs and other economic, local, and macro-cultural factors are likely at play. By considering what causes barriers - language or otherwise - and exploring how we can break them down, we can promote a culture of greater diversity and inclusivity at OHBM.

3 Comments

Roberto Toro

10/19/2020 01:11:22 pm

A very straightforward solution would be to have simultaneous translation. This seems to be the norm at UN, where representatives of the different countries often speak on their own language. I have seen that in scientific conferences as well, and it works really nicely. Of course, we can always put all the burden of the effort on the presenters and send them to take english courses, but that's not particularly inclusive :)

Reply

Fidel Alfaro Almagro

10/19/2020 03:24:45 pm

During one of the Keynote lectures in Rome, 2019, a lady sitting on my right complained loudly about the bad English of the speaker. She said it was not acceptable to have keynote speakers who could not communicate in the language of the conference. While I can partly understand her point, as a non-native English speaker, I felt offended by her comment.

Reply

Lucina Uddin

10/29/2020 06:03:45 pm

A great commentary on this topic just came out recently: https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2020/10/science-s-english-dominance-hinders-diversity-community-can-work-toward-change

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG HOME

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed